It’s not unusual for me to cry on my birthday.

As a kid, I looked forward to this day—the cake, the candles, the feeling of getting older. But now, it’s just a reminder of how much time has passed, and how much I wish I’d achieved by now.

I turned 23 in February, my first birthday since graduating from UC Berkeley and entering this strange, liminal phase of early adulthood when nothing’s really clear. At 22, I finished my honors thesis on John Milton, started writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, and began my graduate studies at the University of Southern California. But still, I can’t shake the feeling that I’m falling behind.

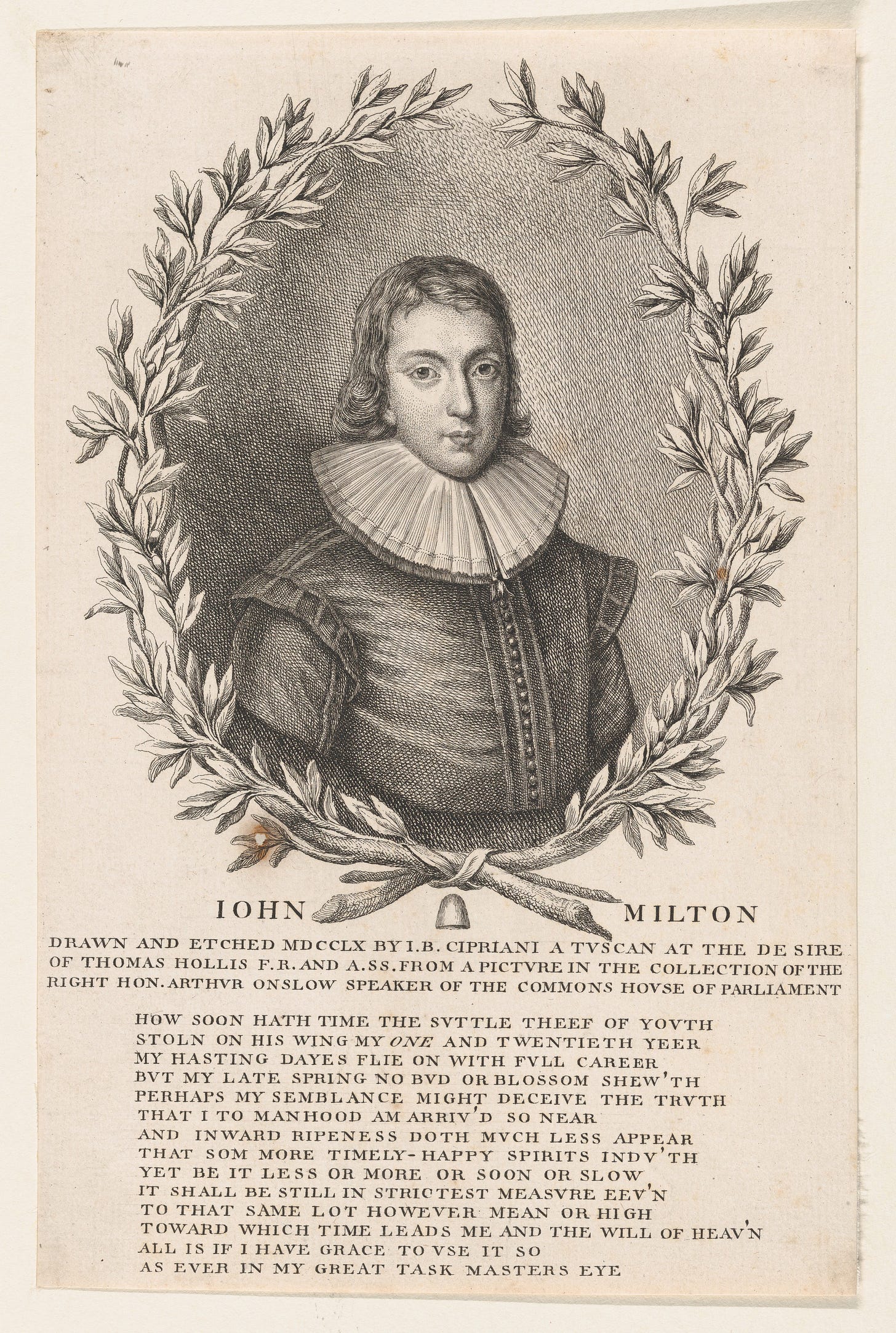

Recently, I rediscovered a poem by John Milton—best known for Paradise Lost—where he reflects on his own anxieties around the age of 23. Written in 1632, “Sonnet 7” captures the same uncertainties many of us feel today about purpose, progress, and the passage of time.1

In today’s newsletter, I’m diving into “Sonnet 7” to explore why it still resonates —whether you’re a college student, a recent grad, or someone just trying to figure it all out.

Before we jump into the text, a quick note: I’ll refer to the poem’s narrator as the “speaker” throughout my analysis. While Milton likely drew from personal experience while writing “Sonnet 7,” it’s important to distinguish between the poet and the speaker within any poem, as they are not always the same.

How soon hath Time, the subtle thief of youth, Stol'n on his wing my three-and-twentieth year! My hasting days fly on with full career, But my late spring no bud or blossom shew'th.

Reflecting on the end of his 23rd year, the speaker imagines Time as a thief stealing away his youth. The word “hasting,” which means “speeding,” highlights how quickly his days are passing by.2 While “career” often refers to a person’s job, it also means “the (rapid) movement of a person or thing along a particular course,” reinforcing the idea of time rushing forward.3 But even as the days progress, the speaker feels unaccomplished and unfulfilled. He’s like a flower that hasn’t only failed to blossom — it won’t even bud.

Perhaps my semblance might deceive the truth That I to manhood am arriv'd so near; And inward ripeness doth much less appear, That some more timely-happy spirits endu'th.

Here, the speaker compares his outward appearance (or “semblance”) with his inner feelings. Even though he looks like a man, he suggests that he lacks the “ripeness” of true maturity. Meanwhile, his peers — whom he describes as “timely-happy spirits” — seem to be flourishing at exactly the right moment. Next to them, the speaker feels like he’s falling behind.

Yet be it less or more, or soon or slow, It shall be still in strictest measure ev'n To that same lot, however mean or high,

Beginning the stanza with “yet,” the speaker alerts the reader to a sudden shift in tone. Rather than dwelling on his perceived shortcomings, the speaker now likens his life to a poem with a predetermined “measure,” or rhythm. Even if the timing of his life feels uncertain right now, he has faith that it will unfold in an “even,” or precise, manner — exactly as it is meant to.

Toward which Time leads me, and the will of Heav'n: All is, if I have grace to use it so As ever in my great Task-Master's eye.

The speaker ends the previous stanza by considering his “lot,” or destiny.4 Building on this idea, he now sees Time — once a thief — as a guide leading him on his path. In the final lines, the poem takes on a more religious tone as the speaker places his trust in Heaven and the “great Task-Master,” or God. Rather than resisting the passage of time, he now views it as part of a divine plan.

Milton went on to write one of the greatest epic poems in the English language, with entire university courses dedicated to his work centuries later. And yet, as “Sonnet 7” suggests, even he felt inadequate at times.

Whenever I catch myself scrolling through LinkedIn or Instagram, comparing my career and life accomplishments with others, I like to return to this poem. It reminds me that my path will unfold “in strictest measure even” — even if I can’t hear the rhythm just yet.

Whether you put your trust in a higher power, in yourself, or simply in time, remember: Everyone moves at their own pace—and there’s something beautiful in that.

Future Reading + Resources

I get all of my keyword definitions from the Oxford English Dictionary. This resource is especially helpful for reading older texts, as it shows how word meanings have changed over time.

If you liked this poem, I suggest reading “Sonnet 19,” which Milton wrote later in life after losing his vision. Similar to “Sonnet 7,” it explores his anxieties about purpose and fulfillment. Yet, in the end, he arrives at a powerful realization: “They also serve who only stand and wait.”5

Milton, John. “Sonnet 7: How Soon Hath Time, the Subtle Thief of Youth.” Poetry Foundation, 1645, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44744/sonnet-7-how-soon-hath-time-the-subtle-thief-of-youth

“Hasting, N. (2) & Adj.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, September 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/2611920910.

“Career, N.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, March 2025, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/3914855094.

“Lot, N.” Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford UP, December 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/9797470075.

Milton, John. “Sonnet 19: When I Consider How My Light is Spent.” Poetry Foundation, 1673, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44750/sonnet-19-when-i-consider-how-my-light-is-spent.